In the middle of a busy restaurant kitchen in London, Sam and Samantha Clark stand contemplating a saucepan filled with cooked, sprouting broad beans. The Clarks, owner-chefs of Moro, have been cooking with dried beans for decades, but it took reading an ancient recipe before they thought to try sprouting them first.

“What’s insane,” says Sam, pausing to taste a bean he has marinated in olive oil, cumin and coriander, “is how much we recognise, how much we don’t and how sophisticated the recipes are.”

He is talking about a newly discovered copy of a 13th-century manuscript titled Faḍālat al-khiwān fī ayyibāt al-ṭaʿām wa-al-alwān (Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib) and written by Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī. Since they opened Moro in 1997, the Clarks have championed the food of the Arabic-Iberian world, but al-Tujībī’s tome is a revelation. “It will affect the way we cook from now on for sure,” says Sam.

Arabic scholars have long known of al-Tujībī’s culinary masterpiece, but it was a chance discovery in 2018 at the British Library, where I work, that allowed all the manuscript’s 475 recipes to be collated and translated. “I thought I was cataloging three medical texts,” says Bink Hallum, Arabic scientific manuscripts curator. “Then I noticed that the writing in the middle of this folio didn’t sound medicinal. It was for food that was . . . delicious.”

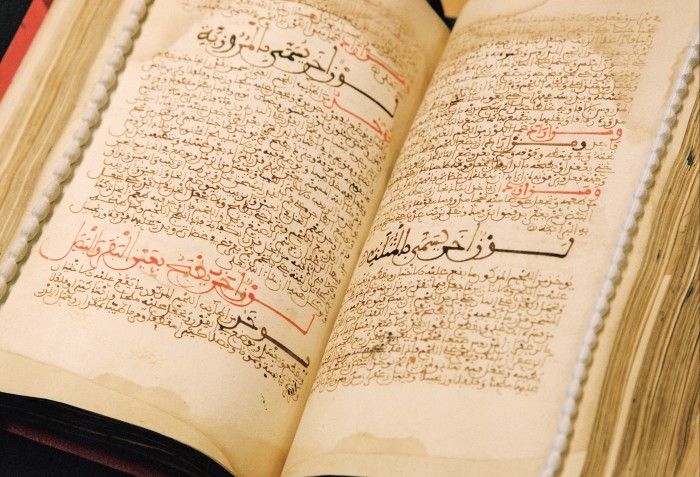

A week before testing al-Tujībī’s recipes, the Clarks meet Hallum and me in a nondescript meeting room in the library’s back offices, looking at the oldest known copy of the original 13th-century manuscript. This one was written in the 1500s, Hallum tells us. Another version, held in the Berlin State Library, was created in the 17th century and one kept at the Royal Academy of History in Madrid was probably created in the 18th century. Hallum has placed the red, leather-bound volume on two black foam rests.

With the help of a couple of “snakes” — strings of weights — Hallum opens the binding in the middle. The Clarks, careful not to touch, lean in while Hallum attempts to decipher the recipe in front of him. One word in particular eludes him. “Turns out spending life reading scientific manuscripts means I don’t have a great food vocabulary,” he laughs. The flowing, elegant writing on yellowing parchment remains clear, despite being 500 years old. “It’s just so beautiful to look at,” says Sam. “It’s more than a recipe book. It’s a work of art.”

The pistachio, walnut and honey halwã made by Sam and Samantha Clark of Moro, one of four recreated by the duo for the British Library Food Season in May from recipes in ‘Delectable Foods’ © Alba Yruela

Hallum unexpectedly uncovered the manuscript while cataloging the library’s Arabic scientific holdings. When he realized what he was looking at, he emailed Nawal Nasrallah, an authority on Arabic medieval cookbooks, based in the US. Nasrallah happened to be in the middle of translating versions of al-Tujībī’s manuscript from the copies located in Berlin and Madrid.

“With a heavy heart, I was resigned to the idea that these incomplete copies were all that was available, and I had to make the best of it,” Nasrallah recalls via video call from her book-lined office in Salem, Massachusetts. Hallum’s message confirming the third and more complete copy was “like a gift from heaven”.

One of only two cookbooks to survive from the 13th-century Muslim-Andalucían world, al-Tujībī’s manuscript details a sophisticated culture. “It is extremely significant,” says Nasrallah. “Compared with other cookery books from this time, it is the most thorough and inclusive of food categories and ingredients, and very well written and organized.” Nasrallah’s translation, recently published as a 900-page hardback, contains footnotes, contextual chapters and a detailed glossary. It took “many, many years” to complete, she says.

According to Nasrallah, Delectable Foods was “obviously written by a person who has actually cooked” and enjoyed the food. Almost every recipe ends with the invocation, “Eat the dish salubriously”.

“I can almost hear his excitement,” says Sam Clark, leafing through Nasrallah’s translation. “It’s like he’s tripping over himself to share different versions of recipes because they are so good.”

Born into a prominent Andalucían family in the prosperous city of Murcia in 1227, al-Tujībī was described by his contemporaries as a “learned scholar and eloquent scribe”. At about the age of 20, along with many others, he was forced into exile when Murcia surrendered to King Fernando III of Castile. When he was 32, al-Tujībī settled in Tunis and wrote the cookery book commemorating the culture and cuisine of his youth. “He wrote his cookbook motivated by a desire to preserve a wonderful cuisine he grew up on,” says Nasrallah, “and which was in danger of being forgotten or lost.”

According to al-Tujībī’s introduction, Andalucíans are “advanced in creating the most delectable dishes”. Arabic influence in Andalucía was greatest between 711 and 1492, as waves of Arab conquest brought settlers from Syria, Yemen and north Africa, along with their customs, culture and agricultural practices. They cultivated rice, saffron, sugarcane, aubergines, sour oranges and grains, in addition to importing ingredients from the Arabic-speaking world.

The 475 recipes in al-Tujībī’s manuscript pay testament to this culinary and cultural diversity. The book is organized into 12 parts, each with multiple chapters. The first focuses on “Bread, Tharayid [bread sopped in rich broth], Soups, Pastries, and the Like” and, among its 16 recipes, is one which “Invigorates coitus”. (The dish consists of a broth made with chicken or starling, flavoured with Ceylon cinnamon, coriander seed, onion juice with breadcrumbs, ginger, black pepper and cloves.) A later section tackles the “meat of quadrupeds” with recipes for beef, mutton and lamb, as well as wild animals like oryx, gazelle and rabbit.

There are 51 recipes dedicated to food preservation such as curing fish, preserving olives and picking turnips. “There are so many things to discover here,” says Samantha, marvelling at recipes calling for ingredients like dessert truffles, yarrow, borage, sparrows, purslane and asparagus. Dishes like “Fried Aubergine Slices Simmered in Sauce and Topped with Eggs” or “Fried [Cheese-Filled] mujabbana” (semolina dough) or “Zalãbiya” (lattice fritters dipped in honey) would not be out of place on Moro’s menu.

Samantha and Sam Clark in Moro, their Arabic-Iberian restaurant in London. ‘What’s insane,’ says Sam, ‘is how much we recognize, how much we don’t and how sophisticated the [Delectable Foods] recipes are’ © Alba Yruela

The Clarks agreed to reproduce four of the manuscript’s recipes for a public event at the British Library Food Season this spring. Sprouting broad beans were on the menu, along with a wafer-thin herb omelette, lentils and “soft, white halwã” (nougat).

“We’ve been making what we call Syrian lentils for 25 years,” says Sam, back in Moro’s kitchen. “But al-Tujībī’s has browned garlic, saffron and vinegar, so it’s going to be different.” To tackle the halwã, Sam looks up a modern nougat recipe.

“It requires such precision,” he says, with a look of disbelief. “How they managed by eye without thermometers is incredible.”

Meanwhile, Samantha takes four large bunches of coriander, pulverises them in a blender and squeezes a couple of tablespoons of vibrant green juice from the resulting mush. She tips this into a bowl of beaten eggs and then adds coriander and cumin powder before transforming the mixture into a wafer-thin omelette.

The Clarks assemble their finished interpretations together on a table. The lentils are a deep, glossy brown and taste earthy and rich. “These show up our recipe a bit to be honest,” says Sam a little sheepishly. Samantha samples the omelette. “It is subtle,” she declares, “but really nice.”

The halwã, sweetened with honey and flavoured with walnuts and pistachios, has a texture like a chewy cloud and is impossibly moreish. “Any one of these could end up on our menu,” says Sam excitedly. Stretching out across the centuries, al-Tujībī’s 800-year-old recipes are a reminder that the past is not always a foreign country.

Moro’s Lentil recipe by Sam & Samantha Clark

-

In a largish saucepan, heat four tablespoons of the olive oil over a medium heat. When hot but not smoking add the garlic, cumin and coriander seeds and fry for a minute until light brown. Then add the coriander stalks and three-quarters of the onions. Soften the onions for 10 minutes, or until sweet.

-

Add the lentils, saffron and water to the pot. Bring to the boil, and simmer for 40-60 minutes or until the lentils are soft and start to mush, becoming sauce-like. Season well with salt and pepper in the last stages of cooking.

-

Remove from the heat and stir in the remaining chopped coriander and the remaining olive oil.

-

Sprinkle a few teaspoons of your favorite vinegar on to the remaining raw onion. Fold half the onions into the lentils and sprinkle the rest on top when serving. Eat with a pitta or flatbread.

Lentils from ‘Best of Delectable Foods’

Take whatever kind of lentils are available to you, wash them, and put them in a new pot with fresh water, olive oil, black pepper, coriander seeds, and chopped onion. Put the pot on a fire to cook.

As soon as the lentils are done, add salt — but not too much — a bit of pounded saffron, and as much as you like of fine-tasting vinegar. Break three eggs into the pot, and as soon as they set and the vinegar boils, remove the pot from fire, empty it into a glazed bowls and eat the dish salubriously, God Almighty willing.

Thin spiced omelettes with vinegar

The Moors fully understood the power of food as medicine. These ingredients are not purely ingredients, they are medicine for body and soul. This recipe makes two omelettes to be eaten as a light meal or as part of a mezze for four.

-

Crack the eggs into a bowl and give them a gentle whisk to break them down a little.

-

Put the garlic in a mortar and pestle and add a pinch of salt (an amount you feel is adequate for the eggs).

-

Pound the garlic with the salt and saffron until it makes a smooth paste. Add all the spices and chopped herbs and pound once again.

-

Add the mixture to the eggs and whisk further. Divide the mixture equally into two bowls. Heat a frying pan (10in/25cm) over a medium heat and add a teaspoon of butter. When the butter starts to color or caramelise, add one of your bowls of egg mix into the pan.

-

Cook gently on one side. We prefer to turn off the heat when the eggs are marginally under-cooked.

-

Slide the omelette on to a chopping board, repeat the process with the remaining egg mix. When the first omelette is cool enough to handle, roll it into a sausage, slice into 3cm portions and put them on to a plate, spiral side up.

-

Repeat the process for the other omelette. Now in a small pan bring the sherry or vinegar to the boil and simmer for one minute with a small pinch of salt. Drizzle the sherry or vinegar over the omelette spirals and serve.

The British Library Food Season takes place during April and May live and online. “Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib: A Cookbook by Thirteenth-Century Andalusi Scholar Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī (1227-1293)”, translated by Nawal Nasrallah, published by Brill, 2021. Hardback ISBN 978 -90-04-46947-1. Ebook ISBN 978-90-04-46948-8

Polly Russell is a curator at the British Library. Follow her on Twitter @PollyRussell1 and Instagram the_history_cook

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Letter in response to this article:

Moorish cookbook is not such a lost world after all / From Francis Ghils, Barcelona, Spain